What Makes the British Party System Spatially Distinctive?

Published: 26 Jan 2025

Tag: Political Science

Ideology is an attribute we associate with many actors and objects. Voters, politicians, political parties, and manifestos are all things which we consider to have, or express, ideology.

This basic fact raises all sorts of interesting theoretical and methodological questions. Do voters and politicians have the same ideologies? Should we expect manifesto ideology to reflect party ideology? How do we measure the ideology of politicians when they are incentivised by things like party discipline not to behave consistently with their ideology? How do we measure these different ideologies?

Measurement in particular has, of necessity, been a source of substantial methodological innovation. I’m going to focus on political parties on this post, and on British parties in particular. For political parties there have been four main approaches so far. The first of these is to take a ‘crowd wisdom’ approach and aggregate the views of voters collected in survey data. The second is to find a means of quantifying party manifestos, such as by econoding left-wing and right-wing statements. The third is to find some way of measuring the positions of legislators - such as through surveys or by scaling outputs of their behaviour such as speeches or votes in parliament; then to aggregate these legislator estimates as an estimate of party ideology. The fourth is to return to survey data, but this time to survey experts.

The last of these approaches guarantees two things. First, all the people you have surveying have access to a lot of information about the ideology of a party, which they translate into the number or category they select in their survey response. Second, because of this, you can typically survey far less people than you would need to in the mass public to get a reasonably stable estimate of party ideology.

Surveying experts is the approach to measuring party positions taken by the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES)1. There’s good evidence from the CHES team that these measures are comparable on a cross-national basis2. In other words, experts understand the main survey scales in the same way: there is a shared understanding of left-right and other scales. I would not be surprised if, over shorter time gaps, these measures are also comparable over time. Because of this cross-sectional comparability (or validity), the dataset is useful for making comparative inferences.

The British Party System

Everyone has a reason why they think their particular political system is special. I am insufficiently contrarian to try to be an exception to this rule and so there are, to my mind, a few reasons why the British system is distinctive. The first is the general history of the British parties, and in particular the British left.

For instance, the British labour movement was much slower to embrace socialism than its continental counterparts. When the Labour Party was finally fully formualted in 1918, it had, from the start, explicitly revisionist rather than revolutionary goals. West European social democratic parties by contrast were defined, to begin with, by a tension between revolutionary rhetoric and reformist practice3. British socialism is thus unique in West Europe in never really having had its origin in Marxism.

Another example is that the British left never really embraced an anti-church stance, so important in the left-wing politics of many other West European countries. In fact, the clash between the Liberals and the Conservatives was defined more by their relationship to different branches of Christianity, rather than one in favour of the church and one against. It is often said - with some justification - that the British Labour party too grew out of nonconformist Christianity. Other salient historical differences exist beyond the left, such as the gradual way in which Britain’s democracy developed, in contrast to the sharp upheavals and sudden changes other West European countries experienced in their path towards liberal democracy. It is difficult to believe that this has not had an impact on the way in which our party system exists today.

The second reason is that the strategic incentives facing British political parties are known to be different to those facing West European parties. Britain’s first past the post electoral system places strong incentives on voters to behave strategically; and to vote only for plausible winners within their constituencies. It’s because of this that Britain largely has a two-party (or a two-and-a-half party) system. Advocates of the system will argue that it produces comparatively stable governments comapred to the coalitions common in the rest of West Europe, and that it is effective in keeping out the political extremes. However, because of the majorities won by single parties, Britain can also experience much more drastic shifts in its politics. It had, for instance, after the second world war the most drastic shift towards economic planning4. Finally, there is evidence that first past the post electoral systems can shift electoral incentives for parties somewhat rightwards5.

A third reason is the simple fact of recent events. Many countries have growing electoral constituencies rooted in a hostility to EU integration - only in Britain has this constituency been sufficiently strong to shift the country out of the European Union. Given the growing importance of EU integration as an issue in West European party competition, it seems more than probable that Britain’s parties will be distincitive on this dimension.

There’s therefore some reason to imagine that the British party system might continue to be distinctive in ways which show up in datasets such as CHES.

Comparing the Parties

The rest of my discussion in this post is based on several plots using data from the CHES. I will use this data to explore one sense in which parties might be distinctive, which is less to do with their history, or the two party system per se. What this data does show, is how the parties are ideologically distinctive when we consider ideology in two senses.

First, in terms of distinct categories - in this case, party family. A liberal party with a similar position to a social democratic party on economics can still be fairly different in its self-image, motivations, constraints, and electorate. Second, in terms of ideological space. We often use spatial metaphors even in colloquial language when thinking about ideology. “I voted for the party closest to my views” and “the party moved away from me” are two common examples.

In CHES, experts rate the positions of parties on quantitative rating scales. They’ll be asked a question containing two opposite poles, and asked to rate the party in question on that scale - usually somewhere between 0 and 10. Using these scales enables me to see how the British parties are unique in spatial terms. To compute the party position, the mean of these ratings is used.

Plotting the Parties on Single Dimensions

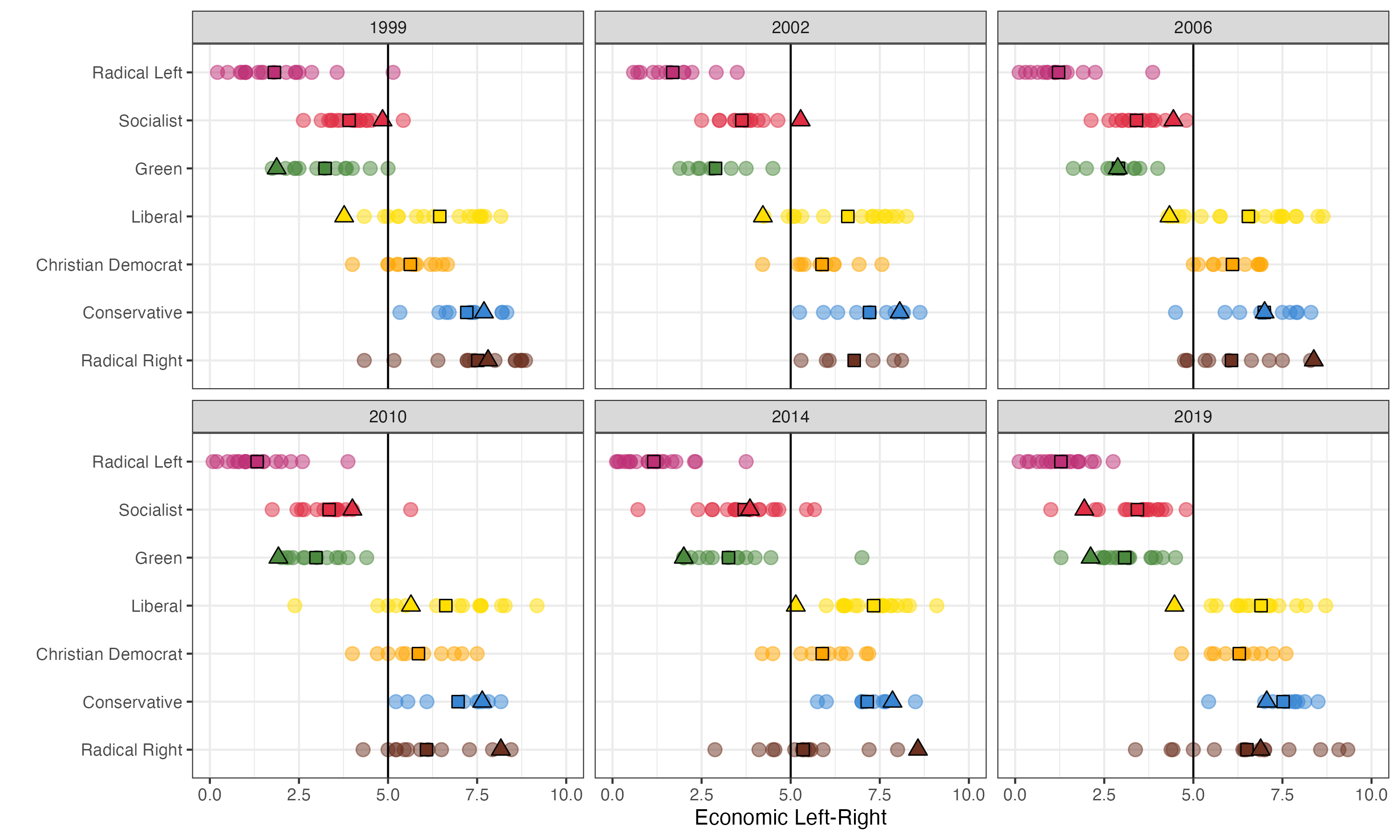

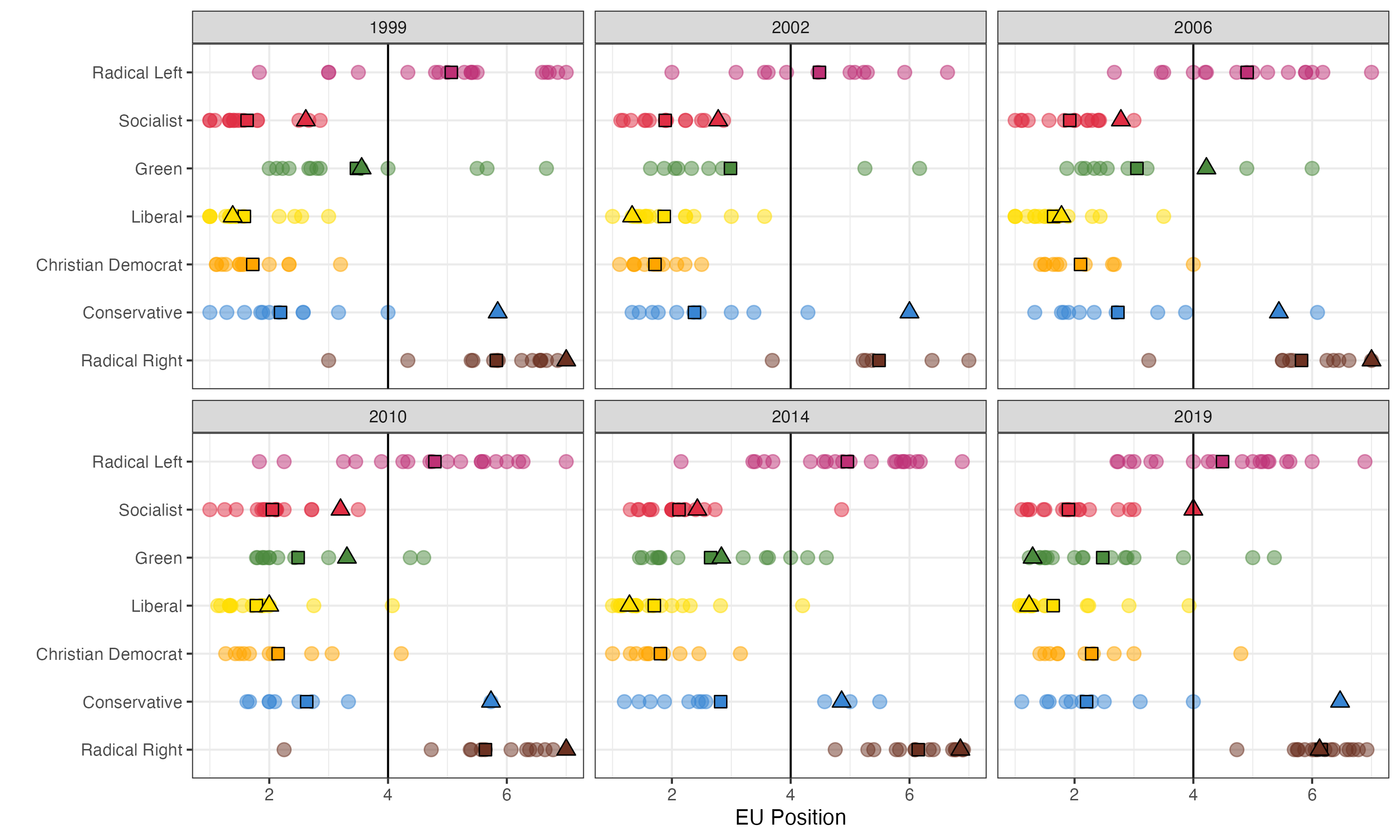

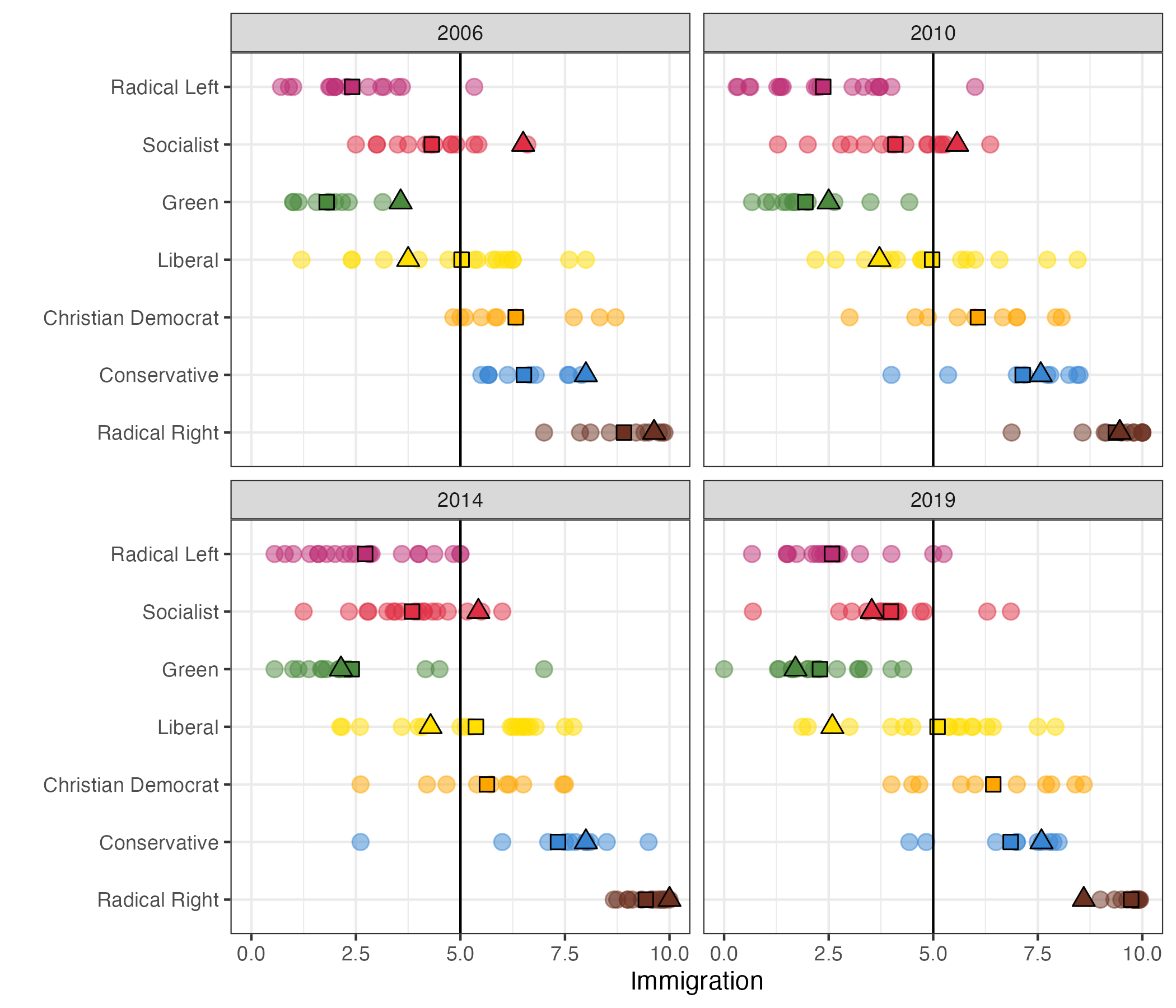

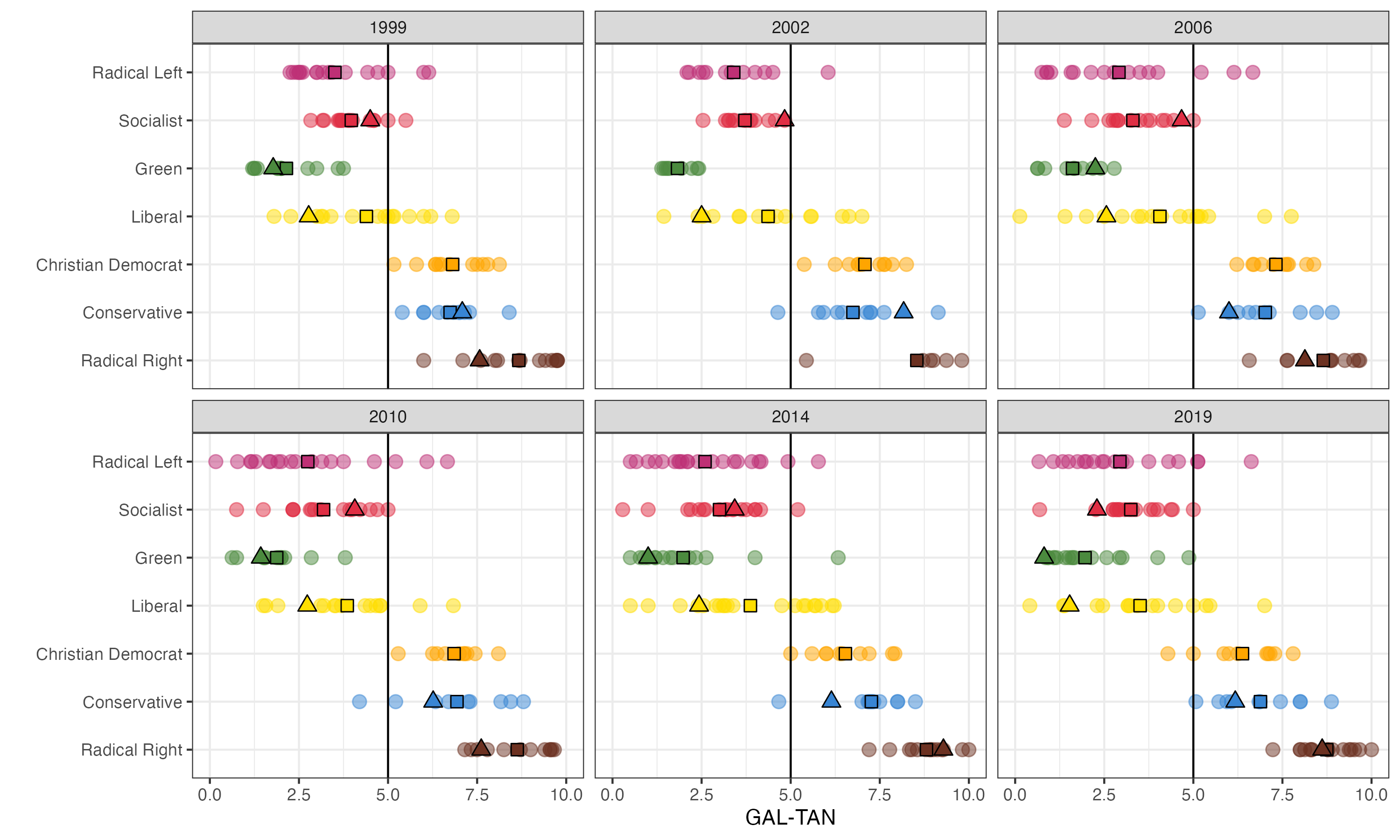

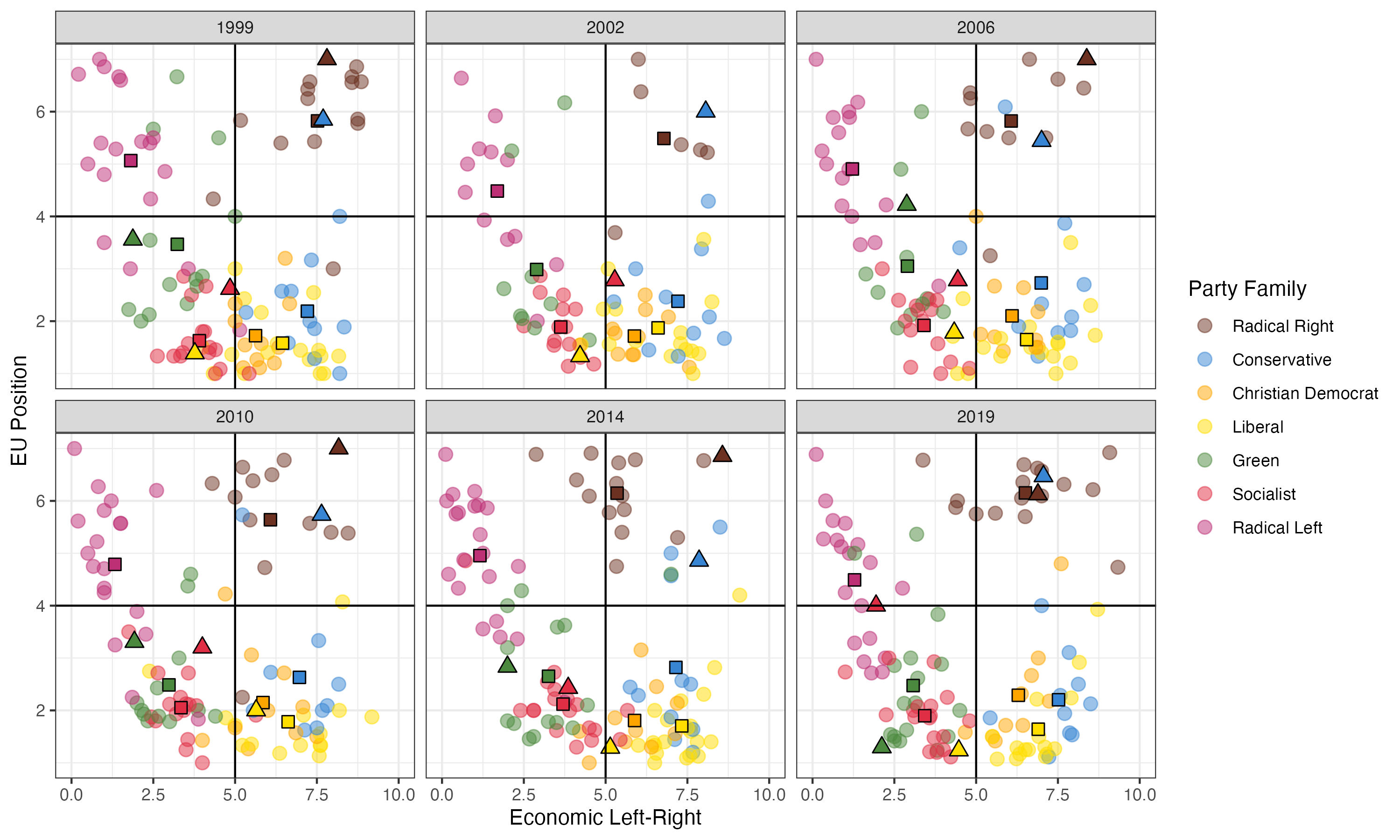

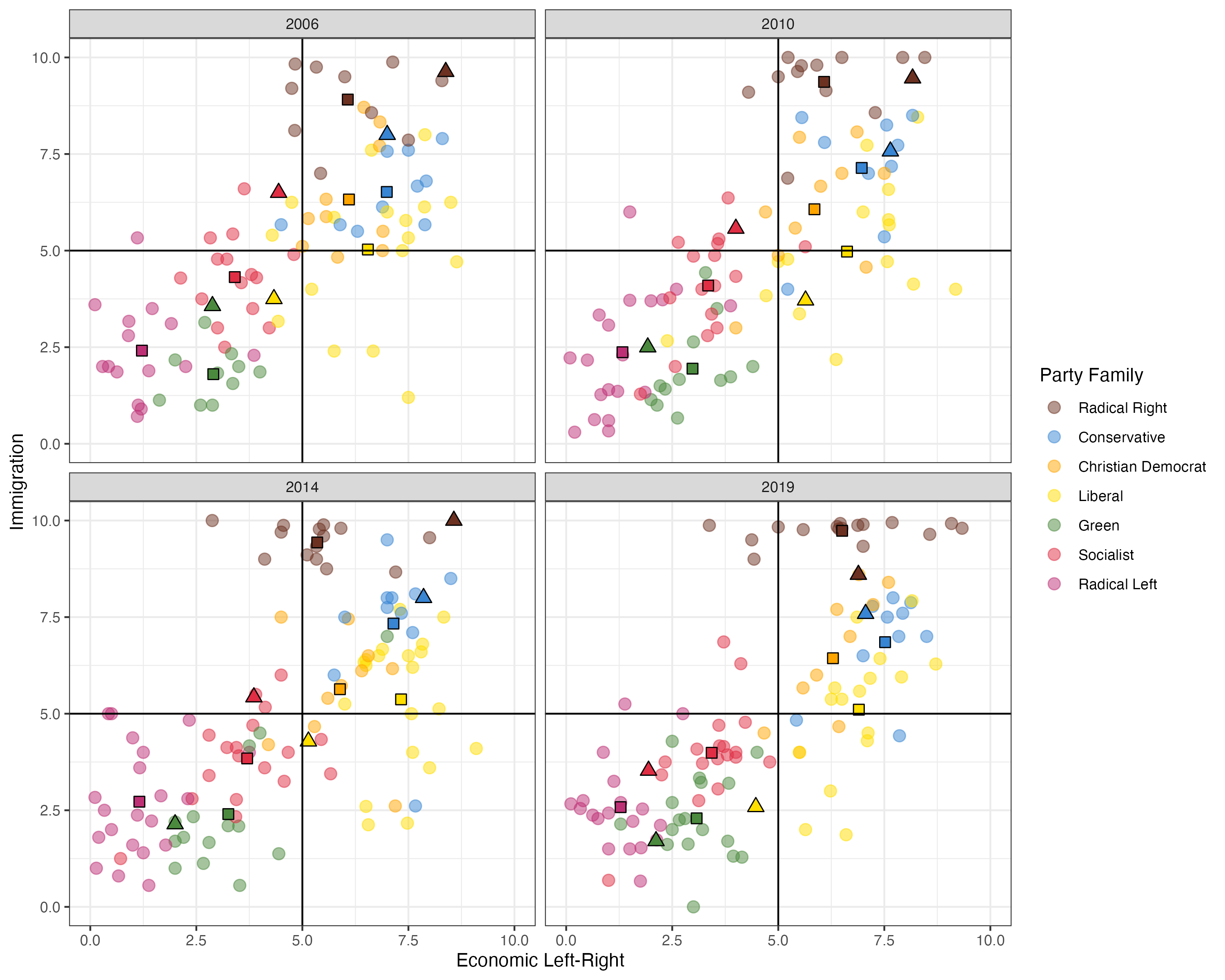

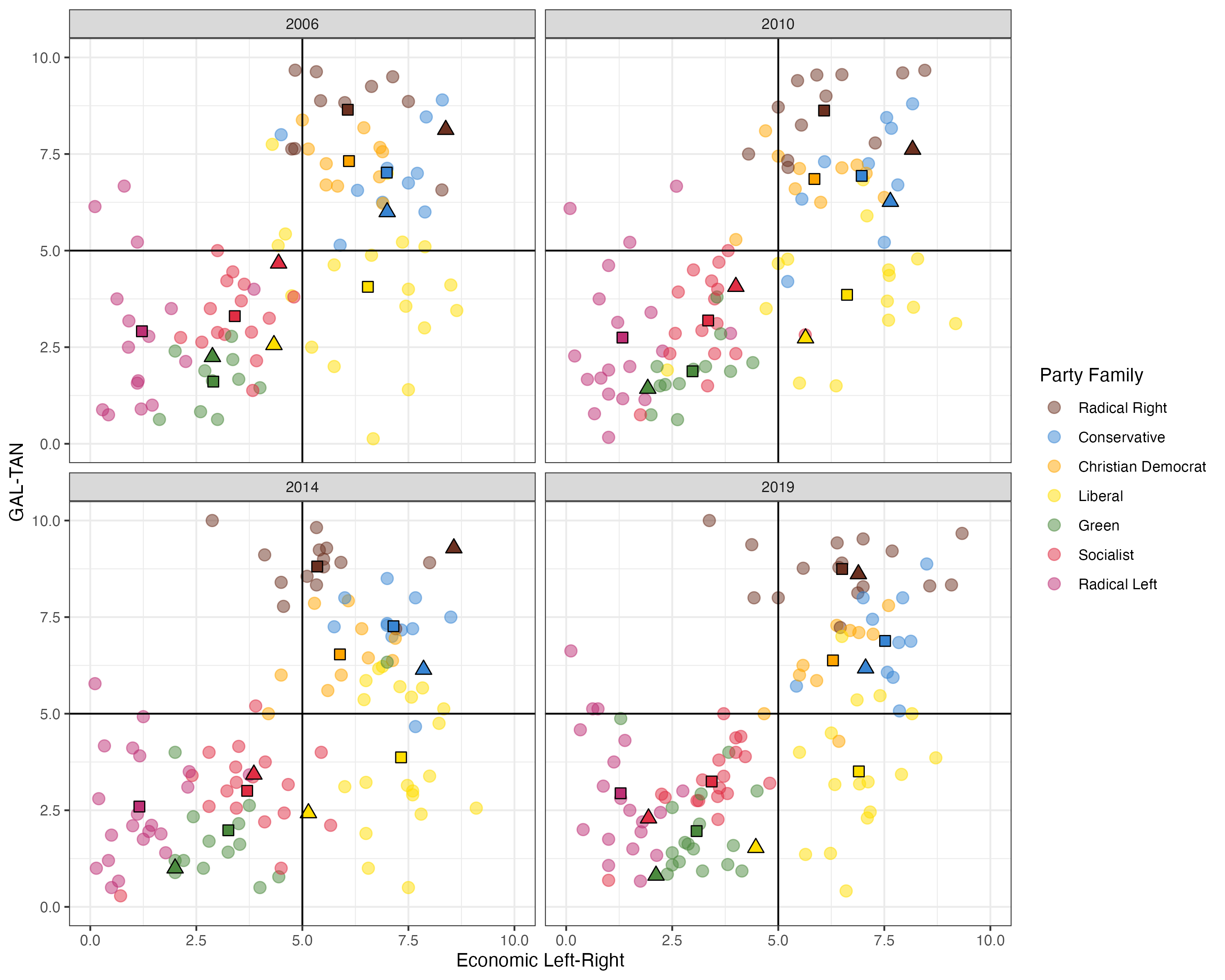

Below I present four grids of plots, each covering one of the most salient issue dimensions in West European politics today. These are the economic left-right dimension, EU integration, immigration, and socio-cultural issues. Except for EU integration (1-7), all of these are 0-10 scales in the survey. I’ve recoded EU integration to range from pro-integration to anti, so that as with other scales the left-coded response is on the leftmost end of the scale.

In each grid of plots, on the y-axis is seven of the biggest party families in European politics. Five of these exist in British politics - these are the socialist, green, liberal, conservative, and the radical right party families. The two families big enough to warrant inclusion but not present in British politics are the radical left and christian democratic party families.

It makes sense that there is no christian democratic family. These parties emerged as parties of the mainstream right in West European countries with large Catholic populations after the second world war4. The corresponding role of mainstream centre-right party is taken by the Conservatives in the UK, though as we shall see, this does have its own implications.

Maybe more surprising at first is the absence of a radical left party. Of course, as outlined above Britain’s left has always been distinctive in that the Labour party never embraced Marxism or revolutionary politics - but this in some ways opens up a clear ideological gap. Even the Communist Party of Great Britain at its height only won 2 MPs in 1945, with a bit over 90,000 voters - and this was really no better than lots of other small parties or groupings in the 1945 election.

On the x-axis in each grid of plots are the parties’ positions on the surveyd dimension in question. As before, this is a mean of the expert ratings. Each point on the plot represents a single political party. Parties in other West European countries are circles and are semi-translucent. British parties are triangles and are fully opaque. The mean position of other West European parties is presented as a fully opaque square. Each plot in the grid represents one survey year for CHES.

The British parties are Labour for the socialst family, the Liberal Demorats for the liberal family, the Green Party for the green family, the Conservatives for the conservative family, UKIP from 1999 to 2014 for the radical right family, and the Brexit Party in 2019 for the radical right family. There is no data for the Greens or for UKIP in 2002 and so these parties are not plotted for this year.

Each grid is subdivided into a plot for each survey year in which that question was asked in CHES.

Economic Left-Right

I’m starting this analysis with economic left-right positions because of its continuing importance in West European party competition. It’s true that we no longer exist in a world where politics is straightforwardly about competiting visions of economic justice and/or efficiency - too many othe dimensions of competition now exist. But economics remains arguably the most salient dimension in party competition.

Looking at the left-leaning parties first, it’s clear that on the economic dimension this is where most of the uniqueness of British politics exists. Within their respetive party families, the Green Party and the Liberal Demorats are among the most economically left-wing in West Europe. The Green Party is closer in position to the radical left family, while the Liberal Democrats are themseleves often (though not always - the Clegg years changed things for a while) closer to the Green Party family. This is arguably one reason why there is no major radical left party in Britain: people who would want to vote for this party are well-served by the Greens, while those who would vote for a moderate green party are well-served by the Liberal Democrats.

Labour as the left’s main party in the UK is equally interesting. Under Blair (leader from 1994 to 2007) it was one of - sometimes the - most right-wing party in the socialist family. This is, plainly, a reflection of Blair’s centrism. Under Brown (leader until 2010) and Miliband (leader until 2015), Labour is much closer to the mainstream of West European socialism. Under Corbyn (leader until 2019) however, it looked more like a radical left party. By now I suspect Labour has probably moved back to the to West European mainstream, or slightly to the right of it - CHES 2024 will be an interesting one for the UK.

The British right, by contrast, shows less idiosyncrasy - at least in the case of the Conservatives. The Conservatives are consistently close to the mainstream of their party family. This does carry some implications for British politics: conservative parties are generally more economically right-wing than christian democratic parties. This might also explain why the liberal democrats are so much more left-wing than their West European cousins: there’s little need for a economically right-wing liberal party if that economic space is already taken by a major conservative party.

It’s more difficult to describe UKIP and the Brexit Party as idiosyncratic in the same way. They are - fairly consistently - among the most economically right-wing of their party family - and in some years extremely so. However, this family is in general fairly idiosyncratic on economics in a way that other party families generally are not. It’s probably fair to describe this as a way in which the British party system is different - albeit among the various differences shown here is arguably one of the less interesting ones.

Europe

The next dimension I looked at is orientations on Europe. As discussed above, the British public is arguably unique in West Europe for the degree and strength of Euroscepticism found within it. This is strongly reflected in the British party system. Equally interesting here is the way in which Brexit has influenced the positions of the British left on European integration.

On the right, the Conservatives are fairly, though not entirely, unique among the conservative party family - and also the christian democratic family, covering the two main flavours of the mainstream West European right. In many ways, on Europe they have consistently been closer to the radical right family. It should be unsurprising that UKIP and the Brexit Party are close to their family on this dimension - it is one of the main dimensions defining this family. I confess one obvious disagreement with CHES - I find it odd that the Brexit Party is placed as less Europsceptic than the Conserservatives in 2019. I also find it odd that the Conservatives in 2010 were placed as more Eurosceptic in 2014, but am less certain in this disagreement.

On the left, the impact of British Euroscepticism is visible on the Labour Party even before Brexit. Prior to 2019, it has consistently been among the more Eurosceptic within its party family, albeit still pro-integration. As of 2019 however, there has been a clear shift in the party’s stance. I think this dimension more than most reveals the difficult of placing a party in a survey. Labour in the sumer of 2019 was much more Eurosceptic than in the general election, by which point it had embraced a second referendum policy. And while true that its leader was more Eurosceptic than the party, the reverse was arguably true of the Conservatives in 2010 - perhaps suggesting where some of these placements might go wrong.

On the rest of the left, the Greens show the most drastic pattern of shifts. In 2006 they shifted towards Euroscepticism - looking fully like a radical left party at this stage. The Greens however shifted back towards being pro-European integration, and in 2019 became as strongly pro-integration as the Liberal Democrats, who have been consistently pro-integration over time. If Brexit has had an effect on the stance of these parties, it is to make them more strongly pro-integration. CHES 2024 will be interesting for the stances of these parties, and what it reveals in terms of how the ideology versus the policies of parties are weighed. The Liberal Democrats for instance remain ideologically highly in favour of integration, but at the time of writing are pushing for Customs Union membership rather than rejoining the EU in full.

Immigration

At this point it’s worth declaring: I’ve frontloaded the most interesting dimensions of party competition. In much of the rest of this post, British parties start to look more like their European cousins. This is true for the most part on immigration, but with a couple of interesting exceptions.

Until Blair’s leadership, the Labour Party had generally been one of the more anti-immigraiton among its family. I was somewhat surprised to see this - what you often hear about the Blair governments now is complaints or regrets about decisions such as allowing new Eastern European EU citizens their right to migrate to the UK immediately. For me this is a point for further reading, but I will admit that this has lead me to speculate on how current issues affect our retrospective evaluations of party ideology. Under Corbyn, this changed, and Labour’s stance on immigration moved much closer to the West European mainstream.

The liberal party family is fairly idiosyncratic on immigration, but the Liberal Democrats, consistent with being among the more left-leaning members of this family, are among the pro-immigration liberal parties. This gap increased in size in 2019, doubtless in connection to Brexit and the strengthening of its pro-European integration stance. Pretty much all other British parties are in line with their families, and their families’ mean position is where you’d expect it to be.

Socio-Cultural Issues

Finally, I will discuss the positions of the parties on socio-cultural issues. In CHES, this is measured using something called the GAL-TAN dimension, which stands for Green-Alternative-Libertarian versus Traditionalist-Authoritarian-Nationalist6. This captures a range of social and cultural issues which generally ‘go together’ (or oppose each other) in certain ways, such as environmentalism, authoritarianism, and nationalism - in other words, what it says on the tin.

As with immigration, the British parties are less distincitve than on the economic and EU integration dimensions as compared to their West European countries. There are even less noteworthy points on this dimension - perhaps that under Blair Labour was again somewhat less liberal, and that the Liberal Democrats are more liberal than their cousins. But on the whole, of the four this dimension shows the least surprises.

Multidimensional Competition

All of the preceeding analysis has examined a single dimension at a time, and for the most part compared British parties against their family. Equally interesting however is to do this in two dimensions. This is already a long post and so I will keep this section brief, but I think some interesting things come out of plotting the economic left-right positons of parties against the other three (non-economic) dimensions.

Left-Right vs EU Position

When plotting left-right against party EU positions - and I hate writing this - a sort of ‘horseshoe’ shape comes out. I don’t want to validate the folk political science of ‘horseshoe theory’ here. This is a fairly dumb notion that the far left and far right are far closer to each other than they are to say, the centre-left or centre-right respectively.

In this plot there’s some truth to this. But it ignores some important features of the plot. First - they are only close in this particular two-dimensional space. Horseshoe theory is really a statement about multidimensional politics. The far left is closer to the centre-left on economics - it would be surprising if this were not true. Throw in the EU dimension however, and when proximity is a function of these two dimensions then which parties are closer or further from which changes. An intersting comparison would be to use a measure like mutual information, and compare it to the pearson’s correlation of the two dimensions. You’d expect the former to be high, but the latter low. On other two-dimensional plots, you will expect both to be high.

For the purposes of this blog post, the other thing this plot does is confirm some of my prior arguments. The Liberal Democrats are in most years closer to socialist and green parties than they are to other liberal parties, with the Clegg years being the main exception. When considering economics and EU position together, the Conservatives look far more like the West European radical right than they do like a West European conservative party. And Labour under Corbyn when considering these two dimensions looked much more like a radical left party.

Left-Right vs Immigration

If the last plot brings up the thought of horseshoe theory, then this plot provides another argument against it. Whether you get a horshoeshoe shape - or a linear one - is a function of which dimension you concentrate on. Party competition on economics and immigration is fairly one-dimensional in Western Europe across all survey years. In plots like these, we would expect high mutual information and a high pearson’s correlation.

As before, it’s interesting which parties are close to which across these two dimensions. Some inferences are stable - the Liberal Democrats still often look more socialist or green than liberal, except under Clegg. Others are not: the Conservatives look far more like a conservative party when not paying attention to the EU dimension.

Left-Right vs GAL-TAN

As before, looking at GAL-TAN after looking at immigration is not particulary interesting or revealing. As with immigration, the positions of parties are fairly linearly correlated. Similar inferences as to party positions apply - I won’t repeat them at this point. Instead, I’ll conclude by noting that the extent to which West European party competition is linear or non-linear strongly depends on the dimensions of competition one is considering.

Footnotes

-

See evidence presented in

- Bakker, R. et al (2014) The European Common Space: Extending the Use of Anchoring Vignettes, The Journal of Politics. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381614000449

- Bakker, R. et al (2014) Anchoring the experts: Using vignettes to compare party ideology across countries, Research & Politics. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168014553502

-

Sassoon, D. (2014) One Hundred Years of Socialism The West European Left in the Twentieth Century, 2014 Edition. ISBN: 9781780767611 ↩

-

Döring, H. and Manow, P. (2015) Is Proportional Representation More Favourable to the Left? Electoral Rules and Their Impact on Elections, Parliaments and the Formation of Cabinets, British Journal of Political Science 47 (1). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123415000290 ↩

-

Hooghe, L. et al (2002) Does Left/Right Structure Party Positions on European Integration?, Comparative Political Studies 35 (8). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/001041402236310 ↩